Considering Kyoto Dialect and Senba Dialect

Posted date:2025-06-16Author:つばくろ(Tsubakuro) Transrator:ポンタ(Ponta)

Category:Kyoto Dialect , Talk about Kyoto

広告

adsense4

At the beginning

When people outside of the Kansai region think of Kamigata language, what comes to their minds is Kansai dialect, Osaka dialect, or Kyoto dialect.

In fact, even those of us who live in Osaka and Kyoto do not often have the opportunity to think about the geographical characteristics or historical tasting of the words we use in our daily lives.

I suspect that the majority of Osaka and Kyoto people vaguely think that the two are similar, but are not sure if they understand the deeper meaning.

Here I will compare and contrast the two representative Kamigata dialects, Kyo language and Senba language, and touch on their respective characteristics and current status.

Where exactly is the Kamigata language from?

I think it is safe to assume that this refers to the language spoken throughout the Kinki region.

It would be appropriate to define it as a Kinki dialect.

The Kinki region refers to the area where the Yamato Imperial Court established its capital in the past, and the five provinces of Yamashiro, Settu, Kawachi, Izumi, and Yamato were the names of the countries at that time.

Today, the three cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe are often lumped together to form the Kinki region, but Kobe itself was little more than a small port until the end of the Edo period.

It can be said that the area developed rapidly after the port was opened at the end of the Edo period (1603-1867) and a foreign settlement was established, making the area a hub for trade.

Therefore, even in the world of classical rakugo, there are no stories featuring Kobe.

Although the name “Hyogo Prefecture” was adopted after the abolition of the feudal

domain, this area was originally called Harima, Settu, Tajima, Awaji, and Tamba before that.

An interesting feature of the Kobe dialect is the pronunciation of the end of words as “~to-o”.

Kobe dialect belongs to the Settu dialect represented by Funaba language, but in Funaba language, it is “~shiteru ka?” In contrast, in Kobe dialect, it is “shitto ka?” which is clearly different from Senba dialect.

The same is ture in the Harima region west of Kobe, while the expression “~to-o”, is not used in Nishinomiya and Amagasaki, which are east of Kobe.

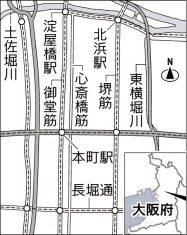

Geography of Rakuchu

Well, I’d like to take Kyoto language from now on.

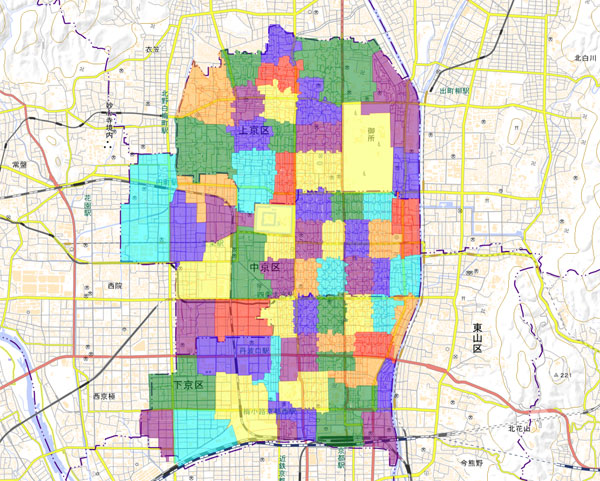

First of all, as to where “Kyoto language” points at, it is the language spoken in Rakuchu, in other words, former Kamigyo and former Shimogyo in terms of administrative divisions (Nakagyo was created from these two Showa 4)

In other words, the language of Rakuchu, the three districts of Kamigyo, Nakagyo, and Shimogyo combined, is called the Kyoto dialect.

Geographically speaking, the northern end is Kuramaguchi, the eastern end is Kamo River, the western end is Sainishi Street, and the southern end is the Tokaido Line.

The area within the section bounded by these four lines is called Rakuchu.

Illustrations image of Rakuchu

This area is served by five train lines: Hankyu, Keihan, Randen, Subway and JR, but it is in contrast to Senba, where the entire area can be traveled only by the subway network.

According to the 2020 Population Census, the population of Rakuchu is as follows.

| The entire Kyoto City | 1,463,723 |

| Kamigyo Ward | 83,832 |

| Nakagyo Ward | 110,488 |

| Shimogyo Ward | 82,784 |

Thus, the total population of the 3 Wards is at best some 280,000, and it is approximately no less than 20 percent of that of the entire Kyoto City.

And Shijo-Kawaramachi at the eastern end is a downtown lined with restaurants.

Although urbanization is indeed progressing, the population density is still 50 times higher than the national average in Japan.

Even today, the noble people of Rakuchu tend to be reluctant to move to other places.

Except for roads and public facilities, the area is almost entirely occupied by townhouses, private houses, and condominiums and other housing complexes, and is characterized by a remarkably high density.

Photo image of a townhouse on Tominokoji

Photo image of streetscape of Sanjo Street

The characteristics of Kyoto language

I have previously introduced in another column the book “I hate Kyoto” by Dr. Shoichi Inoue, which is throughly describing bad words about Rakuchu.

Dr. Inoue was born in Saga in Kyoto, which in the administrative division is Ukyo Ward and is clearly from outside of Rakuchu.

The obi of the book reads, “Well, you, Saga in Kyoto is different from Kyoto…” and the beginning of the book describes an episode in which a farmer made fun of Saga in Kyoto, saying, “In the past, farmers from that area used to come here to fetch manure.”

As he lambasted such experiences, Dr. Inoue himself confesses that he gradually came to despise Kameoka, which is located beyond the Nishiyama from Saga in Kyoto, as a countryside, but the Chinese ideology, which is so focused on regionality, is probably responsible for the splendid hierachical structure of Rakuchu.

There is another major factor that has determined the way of thinking of the Rakuchu people.

It is the relationship with history.

In the 2nd year of Meiji (1869), the emperor moved to Tokyo.

It was just a short visit to see how things were going, and he really intended to come back to Kyoto.

The fact that the retun was procrastinated is a trivial matter.

As proof of this, there is still no imperial rescript on the transfer of the capital.

The Imperial Palace is still in Kyoto.

It would be nicer if the emperor came back to Kyoto every time there was a change of generations.

This is unexpectedly the true feeling of the Rakuchu people.

On the other hand, it is the Naniwa people who are most sensitive to the disposition of the Rakuchu people.

Naniwa people often used it as material for rakugo.

The famous “Kyo-no-bubu-zuke” story is a case in point.

When a customer leaves the restaurant, Rakuchu people, without any intention of serving him or her, always recommend bubu-zuke, saying “Please have some bubu-zuke.”

The plot of the story is that one day, a Naniwa person, fed up with hearing this story, decides, “This time, I will really eat bubu-zuke and go home.”

As usual, the Rakuchu people said, “We don’t have anything for you, but please have some bubu-zuke (pickles) and go home.” The Naniwa person immediately responded, “O-kini, you’re welcome” and have some.

After finishing the first bowl of rice, he asked for a second bowl of rice, but unfortunately, there was only one bowl of rice in the Rakuchu people’s house.

The Naniwa person, growing impatient with the lack of refills, held out a rice bowl and asked, “That’s a nice rice bowl. Where did you buy it?” The Rakuchu people showed him an empty rice chest, and said, “Oh yes. I bought it with this rice chest at a junk shop across the street. The story ends with the answer and the conversation will be a fallout.

As you can see in this rakugo, Naniwa people have a nose for the Chinese thought of Rakuchu people.

Aside from this, it is probably in Hanamachi district that the demand for Kyoto language is the highest today.

Tourists from all over Japan and, more broadly, from all over the world visit Hanamachi and are satisfied to hear the Kyoto dialect used by maiko and geiko when they are playing in the teahouses.

Photo image of maiko

However, it is also true that very few women from among genuine Kyoto residents become maiko today.

The majority of maiko are born and raised in other areas and learn and acquire the Kyoto dialect as a second language, so to speak, in the same way that they learn how to wear a kimono and learn Japanese dance when they enter Kyoto.

So, in this respect, it is fair to say that the modern Kyoto language has become, in a sense, a kuruwa language.

Koji Ohbuchi’s book, “The Real Scary Kyoto Language,” is quite interesting because it analyzes in detail the thought process of Rakuchu people and gives example of the Kyoto language that emanates from it.

Photo of the title for the book “The Real Scary Kyoto Language”

Although Mr. Ohbuchi was born in Etchu, but having grown up in Kamihichiken from his childhood, he is aware that he is not a true Kyoto person, and he objectively examines the social background that gives birth to the Kyoto language.

He said, the thinking logic of Rakuchu people is based on “passive thinking” and they do not express themselves openly, but rather use the advanced tactics of “if the stranger says this, I will say this”, not opposing them face-to-face, but by using a gentle, indirect manner to make them realize.

And to those who don’t understand, they dismiss them by saying, “if you don’t understand the meaning of the words, it cannot be helped.”

I think this is truly hitting the point.

For example, when asked to do something they want to refuse, Rakuchu people often reply, “I’ll think about it.”

This means “I decline” in Rakuchu, but if you don’t understand this nuance and take it seriously, and later ask, “Have you thought about that matter?” he will immediately be taken aback, and in the worst scenario, will no longer associate with you.

And the same is true when someone says to your face, “You are an interesting person, aren’t you?”

The word of Rakuchu people “interesting person” is never a compliment.

This means “I don’t understand what you are talking about.” To put it more bluntly, it is no exaggeration to say that this is tantamount to a sentence of “I won’t go out with you.

Daily conversation between people in Rakuchu when they meet each other on the street.

“Oh, are you going out?”

“Just up there.”

“That’s fine.”

I have no idea what they are trying to say, but this is clearly understandable Kyoto language.

Photo of two older ladies talking with their backs to each other.

The geography of Senba

Senba once referred to the area surrounded by four moats: the west and east Yokobori, Tosabori, and Nagabori.

Its area is only one thirteenth of the area of Rakuchu.

Photo of a map of Senba parcel

About 100 years ago, west Yokobori and Nagabori moats were reclaimed and connected to the land, which led to a rapid increase in the number of factories in the city. As a result, the air quality deteriorated due to soot and smoke, so the merchants of the big stores in Senba moved their families to Tezukayama in the city or to Ashiya and Itami in Hanshin if outside the city.

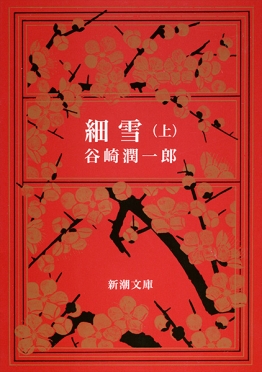

Junichiro Tanizaki’s representative work, “Hosoyuki”, is a novel about the lives of four sisters of such a Senba merchant.

Photo of Junichiro Tanizaki

Photo of the book cover for Hosoyuki

This novel is set in the Kamikata region in the 1935’s and describes the glittering upper-class life of four sisters of the Takioka family, an old Senba family, in the elegant Senba language, in their main Senba home and a branch home in the quiet residential area of Ashiya.

Let’s now look at the Senba language.

Senba language

First of all, it should be noted that while there are a great number of books on the Kyoto language, only a few books have been written on the Senba language?

Where is the reason for that?

This is because Kyoto language has now become a kind of tourism resource.

For many tourists visiting Kyoto, the elegant Kyoto language spoken by geiko and maiko in the Hanamachi district is very attractive.

In other words, today’s Kyoto language has become a “kuruwa” language.

Since the target audience is tourists entering Kyoto, there is a large and unspecified number of people to whom they come into contact with the Kyoto language.

In contrast, the Senba language is used by merchants, and those who come into contact with it are also limited to those who are involved in commerce.

Even looking at just this one point, it is clear that there are significant differences between Kyoto and Senba languages.

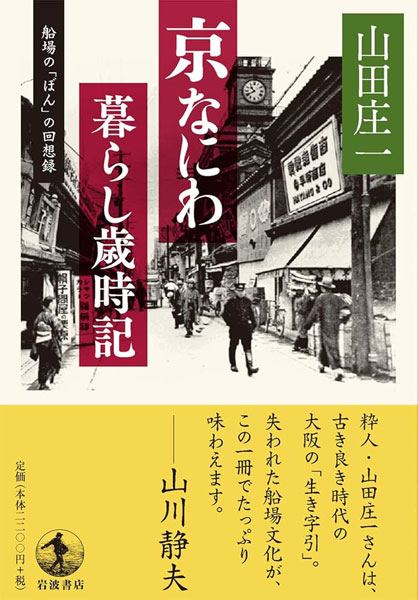

There is very little literature on the Senba language, but a book titled “Kyo Naniwa Kurashi Saijiki” written by Shoichi Yamada is very interesting and informative.

Photo of the book cover for “Kyo Naniwa Kurashi Saijiki”

The author was born in Azuchi town, Senba, in 1925, and his family has been running a kimono shop for generations.

It is noted that shortly after the author’s birth, the Senba and the area around Shimanouchi began to change.

The owner of the merchant house and his family move their residence to the suburbs, leaving only the store in Senba.

Eventually, Osaka was burnt to the ground in an air raid in 1945, and the postwar reconstruction period, the town was lined with high-rise buildings, and Senba’s nighttime population continued to decline.

Therefore, according to the author, the life of merchants and apprentices in Senba featured in Kamikata rakugo all date back more than 100 years.

With that as a basic premise, what left a deep impression on me as I read was the description of the heir to the shipyard.

In ancient times, many families in Senba had their daughters-in-law take over the family business.

If the eldest son succeeded to the family simply because of blood ties, the family’s fortunes could suffer if the successor lacked business acumen.

On the other hand, if they have a daughter-in-law, they can take a time and inspect the character of the person who will be your son-in-law.

It is written that the merchants of Senba thought it more reasonable to let the man they chose to take over the store in this way.

Illustration image of the merchants in Senba

Now, in chapter 4 of the same book, the following words are listed as “Lost Senba Words.”

Let’s extract a few of them.

(noun: a person, the human body, personal effects)

Otogai (chin), debochin (forehead), shibuchin (stingy), neso (gloomy), ojami (handball), kansho yami (fastidiousness), neki (side), habakarisan (thank you for your hard work)

(noun: foods)

Omusi (miso), Oman (manju), oshitaji (soy sauce), okesoku (rice cake to be placed in front of the Buddha)

(verb, adjective, adverb)

Nazeru (to stroke), omasu (to be), zutunai (to suffer, to be without skill), kosobai (to tickle), garando (to be empty), bibincho (to be dirty), enbanto (to be folded)

The author states that these are all words that were used in Senba more than 100 years ago. As a Rakuchu person, Columnist saw this and thought, there were quite a few words I have used.

For example, shibuchin, garando, zutunai, bibincho, habakarisan, and so on. I don’t think all of them are dead words.

The columnist thinks that at present Kamikata rakugo and Shochiku Shinkigeki are two genres that most vividly convey the Senba language of yesteryear.

In particular, the Senba language used in the banquets of Yonecho Katura, a living national treasure, and the kyogen plays of Hiromi Fujiyama, a comedian, has an elegant and gentle flavor that reminds us of the atmosphere of the olden days of Senba.

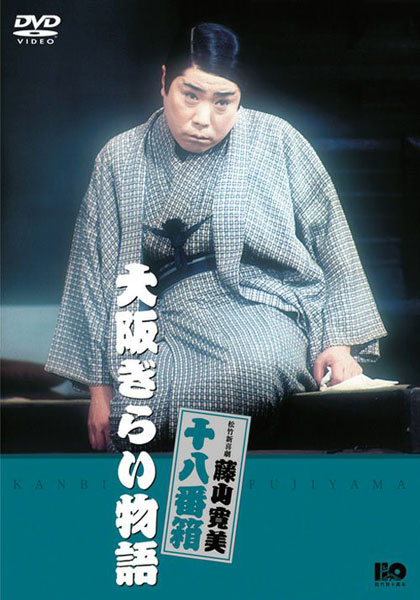

For example, one of Kanbi Fujiyama’s hit Kyogen plays is “Osaka Hate Story.”

This is a comedy set in a big store in Senba during the Taisho era (1912-1926), and in the beginning of the story, when one of the shop assistants is asked to run an errand, he says.

Photo of the DVD package of Osaka Hate Story

“Hona, I’ll be there.”

Rather than “I will go and visit,” “I will stay and visit” is more elegant and comfortable.

In response, the owner of the shop sends the assistant off, saying, “ittoi nah ai”. This is a phrase that can only be said in a town of business.

Another example is the following line from another performance.

“This is something that should not be done in a hurry, but…”

It was used to express a request in a roundabout way to convey that the request should be made in a hurry.

It is a phrase unique to Senba, a town of business.

This kind of exchange took place in daily conversation more than 100 years ago, when the master and his family, as well as the banto, tejiro, and detchi (apprentice), lived together under the same roof in Senba, a place where work and residence were integrated.

Unfortunately, the Senba language is now only preserved in the Kamikata performing arts.

The conclusion

The above is brief description of the characteristics of the Kyoto and Senba language, and you can see that there are remarkable differences between the two today.

It can be said that it was the difference in the historical progression between Rakuchu and Senba that created this factor.

The reason for this is that the population density in Rakuchu is still high and there are still speakers of the language, while in Senba, the owners of merchant houses and their families moved their residences to the suburbs more than 100 years ago and the area was scorched during an air raid.

Today, Kyoto language has become a tourism resource, as represented by gei-maiko (geisha and maiko), but the temperament of the people of Rakuchu, which is the background of the languge, has not change much from the past.

On the other hand, Senba language is now almost extinct, with only a few traces of it remaining in the classical Kamikata performing arts.

References books

1: “Keihan Dialect”, Kenichi Kakutani, Ryukoku Bulletin No. 46

2: “The Real Scary Kyoto Language”, Koji Ohbuchi, 2022, Liberal Publishing Co.

3: The Complete Rakugo Works of Beicho” Beicho Katura, 2013, Sogensha

4: “Hosoyuki”, Junichiro Tanizaki, 1988, Shincho Bunko

“Kyo Naniwa Kurashi no Saijiki”, Shoichi Yamada, 2021, Iwarami Shoten

6: “Hiromi, forever, of Osaka”, Noriko Kibata, 1990, Kamikata performing arts publishing center

Author

つばくろ(Tsubakuro)

I was born and raised in Kyoto and am a native Kyotoite.

When I was young, I longed to visit Tokyo and Osaka, which are more bustling than Kyoto, but as I have gotten older, I have come to appreciate Kyoto a little more.

In this site, I will introduce you to some of the best places to explore Kyoto's food that you might otherwise miss at first glance.