The Origin of Nanban Sweets Beloved in Kyoto

Posted date:2025-08-08Author:つばくろ(Tsubakuro) Transrator:ポンタ(Ponta)

Category:Kyoto sweets , Talk about Kyoto

広告

adsense4

To begin with

The year 1543 is recorded in history textbooks as the year “Portuguese sailors drifted ashore on Tanegashima Island and introduced firearms to Japan.” However, from the perspective of the history of sweets, it can be said that this event also marked the beginning of Japan’s association with Western “sweet sugar.”

The Portuguese and Spanish missionaries who came to Japan for the purpose of spreading Christianity had a particularly significant impact.

In the twelfth year of the Eiroku era (1569), the Portuguese missionary Luis Frois traveled to Kyoto to obtain permission to spread Christianity and met with the powerful warlord of the time, Nobunaga Oda.

The tribute offered at that time was konpeito candy in a flask (glass bottle).

They even offered it as a trump card to secure permission for Christian missionary work, which shows just how valuable konpeito candies were back then.

Nobunaga Oda

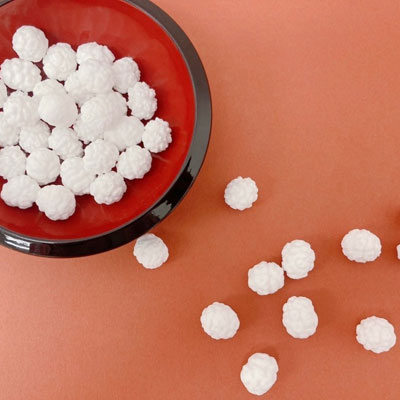

Konpeito

Confeito in Portuguese

Konpeito

Astonished by its unique shape and sweetness, Nobunaga highly praised konpeito and ordered it repeatedly thereafter.

Sugar did not exist in Japan until the arrival of the Nanban people.

Prior to that, confectionery referred to items made from fruits and grains.

Therefore, it can be said that the concept of “sweets” equating to “sweet treats” originated in this era.

The sweetness of sugar became deeply intertwined with the tea ceremony, which was beginning to flourish at that time.

Konpeito candies were also favored by Sen no Rikyu, the founder of the tea ceremony, during outdoor tea gatherings.

Sen no Rikyu

As the tea ceremony gradually spread among the court nobility and warrior class, Nanban sweets made with sugar, including konpeito, gradually became popular among the ruling classes.

For example, in the description in the Taikoki (1625), it said when encouraging conversion to Christianity, missionaries gave wine to drinkers and distributed Nanban sweets like konpeito and castella to those who couldn’t drink.

Since konpeito is essentially a lump of sugar, the court nobles and feudal lords who tasted it for the first time must have been quite astonished.

Even after the Edo period began, Japan relied on Nanban trade for sugar for a long time.

According to records from 1707, one-third of the goods imported from the Netherlands, then a trading partner, were actually sugar.

Therefore, you can probably imagine just how valuable konpeito candy was during Nobunaga’s era.

Now, here’s where you can find a recreation of the konpeito candy that Nobunaga praised back in the day.

Available at “Kyoto University Museum Museum Shop Musepp”.

“Restoration Nobunaga’s konpeito” 1,000 yen

Available by special order Kyoto City Sakyo Ward Yoshida Honmachi TEL: 075-751-7300

Restoration Nobunaga’s konpeito

Among the sweets brought by Nanban people, alongside konpeito, there is another confection that would exert an immensely significant influence on the development of Japanese confectionery culture.

It was castella.

Castella

Pao de Castella in Portuguese

Castella

The ingredients of castella are flour, sugar, and egg.

The use of chicken egg in cooking brought evolutionary changes to Japanese cuisine.

In traditional Japan, the custom of using chicken eggs was absent due to religious taboos.

With the introduction of Nanban sweets and castella, using eggs in cooking became commonplace in Japan. By the Edo period, a cookbook titled “The Hundred Delicacies of Eggs” was even published.

Japanese sweets are made from plant-based ingredients, with the sole exception being chicken eggs.

It can be said that the use of chicken egg undoubtedly broadened the world of taste of Japanese sweets.

Here is the castella specialty shop in Kyoto that has been in business since the late Edo period.

Echigo-ya Tareido

Kyoto City Kamigyo Ward Imadegawa Senbon Higashi-hairu

TEL: 075-431-0289

Flat Sugar

Alfeloa in Portuguese

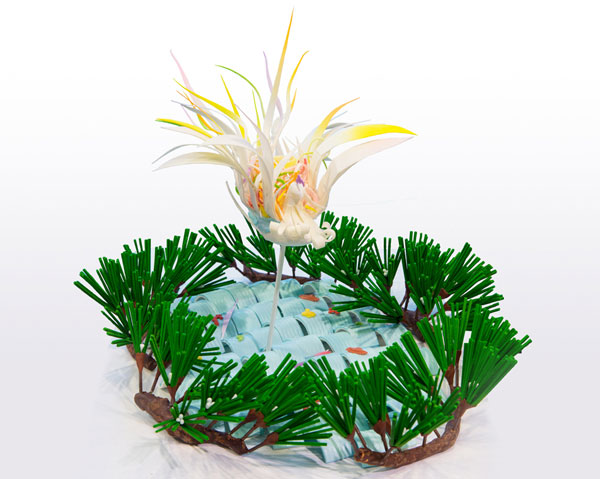

Flat Sugar

To put it simply, it is the hard candy that was introduced to Japan for the first time. Originally, it was a brown candy in the shape of a stick made from molasses.

Alongside konpeito candies, it was highly valued in the tea ceremony and is recorded as having been frequently used at tea gatherings hosted by Hideyoshi Toyotomi.

Entering the Genroku period, seasonal and auspicious items began to be crafted using vibrant colors, eventually evolving into Kyoto’s unique craft confectionery.

Kyoto’s craft confectionery

Flat sugar, like castella, is now a familiar confection among the common people, but in the Edo period it was still a rare and incredibly expensive luxury item.

For example, there is a record that during the banquet held when Emperor Go-Mizuo visited Nijo Castle in 1626, flat sugar was served alongside castella.

Here is the shop in Kyoto where you can easily buy flat sugar today.

Kanshun-do, established in 1865. Flat sugar 1 bag: 400 yen

Kyoto City Higashiyama Ward Kami-horitume town 292-2 TEL: 075-561-4019

Hirousu

Filhos in Portuguese

Hirousu

Originally, it was a sweet that was eaten at Christmas in Portugal, made by mixing flour with sugar and eggs and frying it in oil.

In Kyoto, it was eaten as a sweet called “hirousu” or “hiryozu,” but for some reason, by the late Edo period, it had transformed into a vegetarian dish made from tofu in Edo.

It is now one of the tofu dishes known as ganmodoki.

Chicken Egg Noodles

Flos de ovos in Portuguese

Chicken Egg Noodles

The original inspiration was a Portuguese confection meaning “angel hair.”

Made using only eggs and molasses.

Here is the shop where you can purchase it in Kyoto.

Kyoto Turuya Kakuju-an

Chicken Egg Noodles

1 bundle: 1,080 yen

2 bundles: 2,376 yen

3 bundles: 3,564 yen

4 bundles: 4,644 yen

24 Mibu Nagi-no-miya-cho, Nakagyo Ward, Kyoto City

TEL: 075-841-0751

Bolo

Bolos in Portuguese

Bolo

A baked good made by kneading flour with sugar and eggs.

Some theories suggest it originated from biscuits.

Originally introduced from Portugal with a fluffy, castella-like texture, it underwent unique development during the Edo period to become the crisp, flaky treat we know today.

There are currently three types of Japanese bolo, known respectively as soba bolo, egg bolo, and round bolo.

Among these, soba bolo and egg bolo are known as Kyoto’s famous confections.

Soba bolo was born in the early Meiji period. It is made by kneading buckwheat flour into the standard bolo ingredients of wheat flour, sugar, and eggs, then baking it with a hole in the center (plum blossom shape).

The texture is crisp and light, reminiscent of a Japanese-style cookie.

The savory flavor of buckwheat flour is truly exceptional.

Soba bolo

Here is the shop famous for soba bolo.

Headquarters Kadouka

Kyoto City Nakagyo Ward Anekoji Street Goko-town Nishi-hairu

TEL: 075-221-4907

Egg bolo

Egg bolo, also known as hygiene bolo in Kyoto, is a small, cute, bead-shaped bolo.

Made with potatoes, eggs, sugar, and milk instead of flour, it is easy to digest and ideal for baby food.

Hygiene bolo

Here is the shop famous for hygiene bolo

Nishimuraya Hygiene Bolo Headquarters

Kyoto City Nakagyo Ward Manomachi Nijo-agaru.

TEL 075-231-1232

The conclusion

The dictionary compiled by the Jesuits in 1603 for Portuguese missionaries learning Japanese includes many names of Japanese confections from that era.

Yokan, manju, thin-skinned manju, and other sweet snacks.

Azuki bean mochi, kusa mochi.

Candies, dango, baked wheat gluten snacks, and others.

It is clear that even at this time, Japanese people were already eating sweet confections.

The Nanban sweets brought by missionaries from Portugal, the Netherlands, and Spain during the Azuchi-Momoyama period revolutionized the concept of traditional confectionery through their heavy use of sugar, eggs, and flour.

Nanban sweets were also favored in tea ceremonies and spread among the court nobility and warrior class.

During the Edo period, Japan implemented a policy of national isolation, yet the shogunate simultaneously encouraged domestic sugar production. This led to Nanban sweets developing in a unique Japanese manner.

Eventually, Kyoto confectioners also traveled to Nagasaki, creating new sweets by incorporating the characteristics of Nanban confections into traditional Japanese confectionery techniques.

These confections, possessing a unique flavor distinct from both Western sweets introduced after the Meiji period and traditional Japanese sweets, can still be enjoyed today at Kyoto’s long-established Japanese sweets shops.

References

1: “An Exotic Land in the Ancient Capital” Kyoto Junior Chamber Published 1974

2: “Journal of Food Culture Studies” by Food Culture Research Group, Japan Home Economics Association 2006

3: “The Food Resume” Kansai University Press Published 2022

4: “Japanese sweets” Tora-ya Bunko Published 1960

5: “The Genealogy of Japanese Sweets” by Takaya Nakamura Published by Tankosha, Published 1967

Author

つばくろ(Tsubakuro)

I was born and raised in Kyoto and am a native Kyotoite.

When I was young, I longed to visit Tokyo and Osaka, which are more bustling than Kyoto, but as I have gotten older, I have come to appreciate Kyoto a little more.

In this site, I will introduce you to some of the best places to explore Kyoto's food that you might otherwise miss at first glance.