Secret Stories Surrounding the Capital Relocation and Makimura Masanao

Posted date:2025-08-04Author:つばくろ(Tsubakuro) Transrator:ポンタ(Ponta)

Category:Talk about Kyoto

広告

adsense4

To begin with

It’s needless to say current Japan’s capital is Tokyo, however, deep down in the hearts of true Kyoto natives, the real feeling seems to persist: “No, even now, the capital is still Kyoto. His Majesty the Emperor will surely return to Kyoto someday.”

Many people are surprised to hear this, this sentiment in Kyoto people is said to be actually not entirely off the mark.

Let me now explain why.

The Hidden Story Behind the Move of the Capital to Tokyo

The first person to utter the words “relocate the capital” was Toshimichi Okubo, a senior retainer of the shogunate.

It took place in January, 1868 (Meiji 1).

Why did the idea of relocating the capital arise?

First and foremost, in order for the newly established government to seize power, it was necessary for those in authority to demonstrate to those around them that they maintained a close relationship with the emperor, the symbol of power.

For that reason, it was truly inconvenient for the rulers of the time to have the emperor residing deep within the old-fashioned Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Furthermore, it was suggested that Kyoto, surrounded by mountains and experiencing extreme temperature fluctuations, is indeed a rather peculiar place.

In contrast, the shogunate officials of the time argued that Edo and Osaka possessed far more suitable conditions for a new capital.

Initially, Toshimichi Okubo proposed that Osaka should be the capital.

This was because Osaka had been the center of Japan’s economy since Edo period, famously known as the “kitchen of the nation.”

However, on the other hand, there were criticism that Osaka was too close to Kyoto.

In the end, it was agreed that Edo was the most suitable place for the new capital.

The reason for this was that Edo made it easier for the rulers to establish close ties with the emperor.

That way, the power they could wield naturally became more solid.

Moreover, Edo had already effectively established itself as the center of Japanese politics, having been the seat of the shogunate government.

The towns of Edo were densely populated and bustling with activity, with daimyo residences standing side by side.

The new government also considered that utilizing these mansions as government offices and administrative buildings would eliminate waste.

Under these circumstances, in March 1868 (the first year of the Meiji era), the emperor set out for Edo.

The official reason given was that he was going to view Edo.

At first, the people of Kyoto never dreamed that the capital would be relocated.

They saw off the emperor and his entourage with the feeling of “Hurry home.”

However, before long, a sense of suspicion began to surface in the minds of the Kyoto people: “Wait a minute, isn’t something a bit off here?”

His Majesty the Emperor has yet to return, Edo changes its name to Tokyo, and the new government institutions also move to Tokyo.

Well, the people of Kyoto began a frantic and fierce opposition movement.

It was absolutely unacceptable that Kyoto should ever cease to be the center of Japan.

After spending over 40 days touring Edo, the emperor returned to Kyoto for the time being.

However, the decision within the government to establish Tokyo as the capital was virtually final, and in September of that same year, the emperor would once again head for Tokyo.

This time, the empress has also moved to Tokyo.

No matter how much they made excuses saying “I will back soon,” Kyoto people wouldn’t believe them anymore.

The people of Kyoto, literally thrown into panic, distributed petitions, formed protest groups opposing the capital’s relocation, and repeatedly staged demonstrations against the Imperial Palace.

Kyoto Prefecture officials kept trying to muddle through with excuses, but finally gave in. On March 3, 1870 (Meiji 3), they gathered resident representatives to explain the reasons for the capital’s move to Tokyo and that, in exchange, they had received a temporary tax exemption and a 150,000-yen fund.

To put it simply, Kyoto at that time was like a husband who had been handed an ultimatum unilaterally by his long-time spouse.

What’s interesting is that despite calling it the relocation of the capital to Tokyo, not a single official document has ever been issued to this day and the capital relocation proceeded in a manner akin to a kind of ex post facto approval – simply the emperor moving to Tokyo.

The capital move to Tokyo was never sanctioned by imperial decree. This is why Kyoto residents believed, “His Majesty the Emperor will return eventually. His presence in Tokyo now is merely a trial run.”

Well, having lost the emperor, Kyoto had to make a living on its own, using the 150,000-yen severance payment it received from the government as seed money.

At that time, over one-third of Kyoto’s cityscape had been reduced to ashes during the Hamaguri Gate Incident, a war-torn event of the end of the Edo period commonly known as the “Dondon-Yake.”

Following this period of war, in 1897 (Keio 3), political authority was restored to the Imperial Court, and the Imperial Edict of Restoration of Imperial Rule was issued.

At first, the people of Kyoto held strong expectations that “this would make Kyoto the political center of the new government in both name and reality.”

However, in 1869 (Meiji 2), the decision to move the capital to Tokyo became final.

This left extremely profound impact on the people of Kyoto.

This was because the relocation of the capital caused the Imperial Household, along with six branch imperial families, 137 noble families, and 97 feudal lords’ residents, to dismantle their estate and move to Tokyo. All these residences were left unoccupied.

In particular the Imperial Palace measured 600 meters east to west and 1,200 meters north to south, covering an area of 72 hectares. Within it, the imperial residences and the residences of the nobles were densely packed, but all of them became uninhabited estates.

Soon, the walls crumbled, the gates collapsed, and within just a few years, everything except the Sento Palace lay in ruins.

Furthermore, the economic fear that Kyoto would become a dead city grew immensely as the Nishijin textile industry and related businesses, which had dealt with these imperial families and noble families, suffered devastating blows.

The population, which had been 350,000, had plummeted to under 200,000.

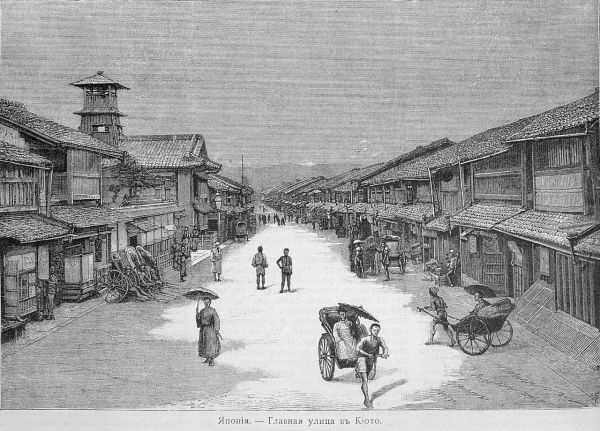

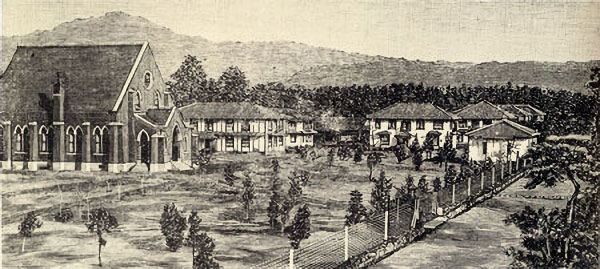

City of Kyoto in Meiji Era

Transforming Kyoto into an Industrial City: Governor Masanao Uemura’s Execution Power

Under these circumstances, in 1869 (Meiji 2), a figure who would play a crucial role in Kyoto’s reconstruction assumed the position of senior adviser, a role assisting the governor.

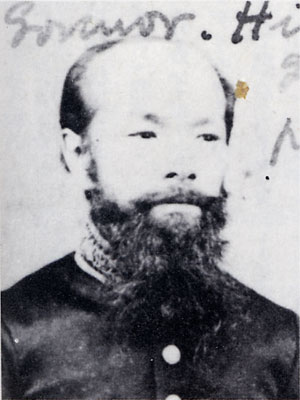

That is Masanao Makimura.

Masanao Makimura

Masanao Makimura was a person specially dispatched by Takayoshi Kido, who was concerned about Kyoto’s decline.

Takayoshi Kido was also from Choshu, as was Masanao Makimura. During the turmoil of the end of the Edo period, Takayoshi Kido placed great trust in the young Masanao Makimura as a spy.

Impressed by Musanao Makimura’s exceptional abilities for a spy, Takayoshi Kido highly valued his skills and sent him to Kyoto.

In order to meet Takayoshi Kido’s expectations, Masanao Makimura, dispatched to Kyoto, implemented one measure after another to revive the city during his twelve-year tenure.

It is fair to say that Kyoto’s very existence today is largely due to dedicated efforts of Masanao Makimura, whose achievements span an incredibly wide range.

His achievements are following below:

1. Fulfillment of Educational System. Opening the Japan-first elementary schools. (Meiji 2)

Established Bangumi elementary schools

Subsequently, a four-year junior high school aimed at gifted education was established. (Meiji 3)

In addition, to enhance language proficiency, language schools for English, German, and French have been established.

(Meiji 3 – Meiji 4)

In addition, he established women’s sewing workshops. (Meiji 6)

The Women’s Arts School was essentially the Prefectural Women’s Technical Arts School, and three types of Women’s Arts Schools were established.

The Women’s Arts School

Upper-class Women’s Arts School

An educational institution for girls of the nobility and samurai class.

Lessons in English, calligraphy, sewing, arithmetic, and tea ceremony were held.

This evolved into the pre-war Kyoto Prefectural Girl’s School and is now Kyoto Prefectural Ouki High School.

Yujo Women’s Arts School

It was established within the Gion entertainment district.

The subjects taught included cooking, calligraphy, flower arrangement, etiquette, sewing, sericulture, and weaving.

Town Girls’ School

The curriculum included sewing, sericulture, and weaving.

However, the primary purpose was to prevent girls from becoming delinquent.

Furthermore, the founding of Doshisha English School (present-day Doshisha University). (Meiji 8)

Doshisha English School

Kyoto Prefectural Normal School (present-day Kyoto University of Education) opened. (Meiji 9)

Kyoto Prefectural Medical School (present-day Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine) and Nishi Honganji University (present-day Ryukoku University) opened. (1879)

Kyoto School of Painting (present-day Kyoto City University of Arts) opened. (1880)

Yukichi Fukuzawa visited Kyoto in 1872 (Meiji 5) for an inspection of the city and wrote “Notes on Kyoto Schools.” In it, he highly praised the advanced nature of various schools, starting with the elementary school system.

2. Establishment of Nishijin Products Company (1869)

Nishijin Silk Weaving Factory

Nishijin textiles, long regarded as Japan’s premier high-end fabrics and a mainstay of Kyoto’s industry, faced a life-or-death crisis when the war-torn late Edo period devastated the Nishijin district.

Makimura believed that reviving Nishijin was an urgent necessity for Kyoto’s industrial recovery and established the Nishijin Product Company. (Meiji 2)

Furthermore, he sent three artisans to study in France, a leading nation in textiles.

They learned the latest techniques locally and brought back several types of the most advanced looms, including Jacquard looms purchased on site.

Among them, the Jacquard loom was four times faster than previous looms, and the precision of its finished products was truly remarkable.

These new techniques and looms were then transferred to the Seimi Bureau mentioned next, where a weaving factory was established as a branch of the bureau.

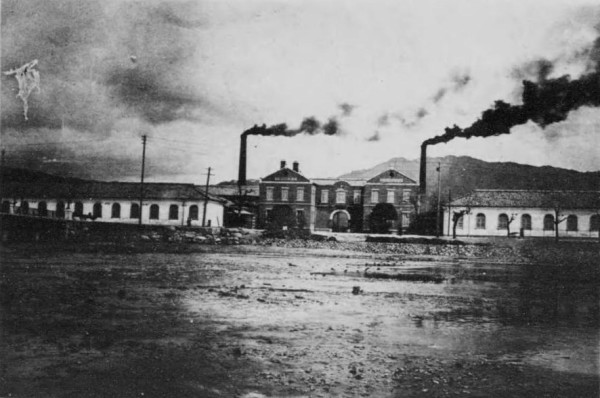

3. Seimi Bureau (Meiji 3)

Seimi Bureau

The word Seimi is derived from the Duch word “Chemie”, which means chemistry.

The purpose of Masanao Makimura’s establishment of it was to open Japan’s first RIKEN institute attached to a school.

The work at this institute included full-scale inventions and research on soap, sparkling water, beer, cloisonne, glass, photography and so on.

They also brewed and sold beer made from famous water in Rakuto-Kiyomizu.

For the brewing of the beer, they have conducted full-scale survey of the water quality in the city of Kyoto to select the best fresh water in Kiyomizu.

Meanwhile, more than 160 students were learning physics and chemistry at Seimi Bureau.

The instructor was Gottfried Wagner, who was invited from Germany.

4. Kangyo-jo (Meiji 4)

Kangyo-jo

The job was an industrial comprehensive headquarters that involved all aspects of prefectural government except police and education.

The job description is as follows.

・Development and operation of mines.

・Development and guidance of wastelands.

・Making of good forests.

・Livestock promotion

・Management of taxes on raw silk, cars, horses, and sake etc.

・Management of playgrounds

Specifically, a leather factory (1871), a cattle breeding farm (1872), a sericulture plant (1872), a cultivation experiment station (1873), a silk mill (1873), a combined pharmacy and so on were opened and it even went to so far as to recycle garbage by opening Kakai-sho (a garbage dump) (1875) (it later became the Kyoto Environment Bureau).

And on the other hand, Makimura promoted cultural activities with temples and Gion involved.

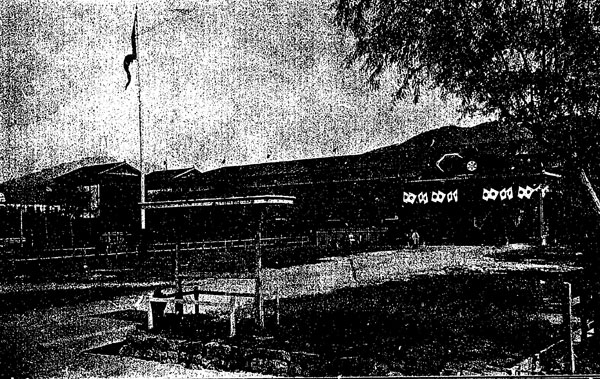

5. First exposition held in Japan (1871)

The exposition

As part of the industrial promotion policy for the development of Kyoto’s industries, the first exposition in Japan was held in the precincts of Nishi Honganji Temple with the cooperation of influential merchants living in Kyoto. (Meiji 4)

Although the exhibits at that time were all antiques, and the event was criticized as an antique market, it was highly praised for the spirit of Kyoto’s townspeople, who were the first in the country to tackle an unknown event and make it a success.

Makimura was so impressed that he established the Kyoto Exposition Company immediately within that year. (1871)

Next year (1872), the first Kyoto Exposition was held in three venue, Nishi Honganji Temple, Kenninji Temple, and Chion-in Temple, and during the 80-day exposition, 40,000 people visited there and 2,500 items were on display.

Geisha and maiko from Gion were invited to perform dances to enliven the atmosphere.

This was the beginning of today’s “Miyako-odori.”

From the following year, starting in 1876, these expositions were moved to Imperial Palace and held annually.

In 1878, a permanent exposition venue was completed next to the east of the Imperial Palace.

The designer was Gottfried Wagner, a German advisor who taught at Seimi Institute.

This exposition building was later moved to Okazaki, changing its name to Kyoto Kangyo Kaikan.

6. Shusho-in (Meiji 6)

Shusho-in

Makimura took a deep interest in public libraries early on.

He devoted extraordinary energy to the establishment of the prefectural library, which he named Shusho-in, and completed the construction of an imposing two-story Western-style library. (Meiji 6)

When the library was first opened, it had 2,577 Japanese and Chinese books and 6,120 Western books.

Makimura also contributed to the proliferation of print culture.

When woodblock printing was the only method available, he was among the first to import movable type printing presses from Germany.

This brought movable type printing to the newspaper industry.

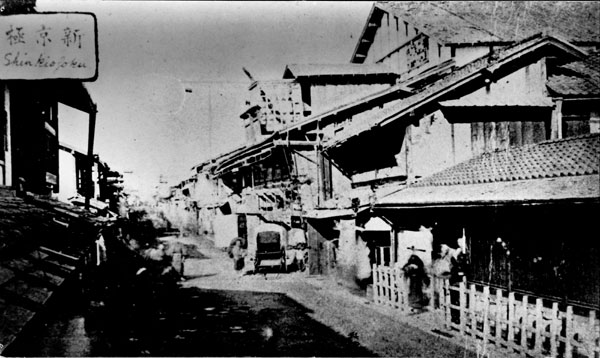

7. Construction of Shin-kyogoku (1872)

Shin-kyogoku in Meiji era

Masanao Makimura noted that during the Tensho era, Hideyoshi Toyotomi concentrated temples along Teramachi Street, resulting in temple fair stalls lining the temple grounds and the Teramachi district flourishing.

To boost the morale of Kyoto citizens, whose spirits had waned after the capital’s relocation to Tokyo, he purchased land from temples adjacent to the east side of Teramachi Street and constructed a new road stretching approximately 500 meters from Sanjo to Shijo.

This led to the creation of Shin-kyogoku.

He aggressively invited theaters, joruri performances, and vaudeville halls to establish operation.

As a result, restaurants and other businesses began opening nearby, and within a few years, Shin-kyogoku became Kyoto’s premier entertainment district.

8. Capital Dance (Meiji 5)

Capital Dance

It began as a side attraction at the First Kyoto Exposition held in 1872.

Masanao Makimura wrote the lyrics, and the then-emerging third-generation head of the Inoue school, Yachio Inoue, conceived a new performing art style called “Capital Dance,” inspired by Ise’s Turtle’s Baby Dance”.

Since then, it has been held annually to this day.

The conclusion

The above provides a brief overview of the major achievements of Masanao Makimura.

In advancing these projects, Makimura wielded his formidable skills with a forcefulness that could be described as aggressive.

For example, it cannot be denied that he also exhibited excessive tendencies, such as attempting to sell the Phoenix Hall at Byodoin Temple in Uji for 2,000 yen, or banning the Girls’ Festival and Boys’ Festival as outdated customs, thereby impoverishing the livelihoods of doll-making artisans and merchants.

However, the mission entrusted to Makimura was, above all else, to revitalize the declining city of Kyoto.

To achieve this, it could be said that the era itself demanded a figure capable of exercising strong leadership.

Moreover, the period in which he was active was one when the foundations of local government were remarkably weak, demanding resolute decision-making and strong execution from those in leadership positions.

Under such circumstances, Masanao Makimura was able to fully unleash his innate drive for action.

Nevertheless, as the era progressed and the systems of a modern nation-state and local government took shape, Makimura’s authority gradually diminished.

Eventually the autocratic Masanao Makimura began clashing with the members of the established prefectural assembly and he eventually became a councilor in the Privy Council in 1881 and relocated to Tokyo.

However, it can be said that the foundation for Kyoto’s modernization was undoubtedly laid during the approximately twelve years from 1869, when he was assigned to the post, until 1881, when he left as a councilor of the Privy Council.

During that period, he actively introduced advanced Western technology, applying it not merely for industrial development alone, but extending its influence to encompass broader educational and cultural initiatives.

This enabled Kyoto to overcome the crisis of being abandoned as the capital in the early Meiji period through its own unique approach, transforming it from a city relying solely on tradition into a modern Kyoto.

Some refer to the period of Kyoto politics from 1869 to 1881 as the “Makimura Era,” and indeed, his achievements during this time certainly warrant such a designation.

References

1: “Foreign Land in Ancient Capital”: Kyoto’s Face You didn’t ” Kyoto Junior Chamber Published 1974

2: “The Capable Governor Who Revived Kyoto: Masanao Makimura, Who Devoted Himself to Civilization and Enlightenment” by Toshiro Mitunaga, published by Tankosha, 2009

3: The Restoration: The Iron-Fisted Governor Who Saved Kyoto: Masanao Makimura and the Townspeople” by Tetuo Akita, published by Shogakukan, 2004

4: “The History of Kyoto, Volume 7: The Turbulent Era of the Meiji Restoration” Kyoto History Compilation Office, Kyoto City, Published 1980

5: “Asahi Encyclopedia of Japanese Historical Figures” Asahi Shimbun Publishing Published 1994

6: “Kyoto Prefecture’s Centennial: A Century of Prefectural People’s History” Edited by Ryoji Igata etc. Yamakawa Publishing Co., Ltd. Published 1994

Author

つばくろ(Tsubakuro)

I was born and raised in Kyoto and am a native Kyotoite.

When I was young, I longed to visit Tokyo and Osaka, which are more bustling than Kyoto, but as I have gotten older, I have come to appreciate Kyoto a little more.

In this site, I will introduce you to some of the best places to explore Kyoto's food that you might otherwise miss at first glance.