Gourmet Soseki savors Kyoto cuisine

Posted date:2025-07-28Author:つばくろ(Tsubakuro) Transrator:ポンタ(Ponta)

Category:Kyoto Gourmet , Talk about Kyoto

広告

adsense4

To begin with

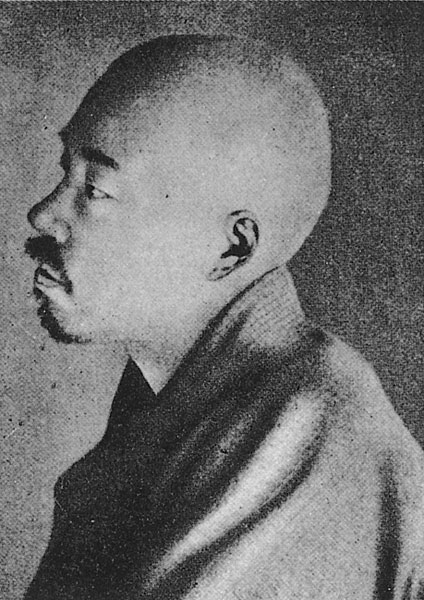

Soseki Natume, a literary giant of the Meiji era often mentioned alongside Ogai Mori, is known for his numerous works that delicately depict the complexities of human psychology and pose profound questions about life and its very meaning.

However, on the other hand, Soseki was also a tremendous glutton.

Soseki Natume

For example, even as he lay dying, Soseki repeatedly begged his family at his bedside, “Give me something to eat.”

About ten days before his death, while bedridden, he pestered his wife Kyoko, saying, “I’m hungry, give me something to eat,” and consumed bread, milk, fruit juice, and ice cream.

According to the book “Father Soseki Natume” by Shinroku Natume, Soseki’s second son, the last words he uttered on his deathbed were the previously mentioned “Give me something to eat.”

When the doctor permitted him to have wine at least, Soseki drank it and uttered just one word: “Delicious.” Then he drew his last breath.

y the way, Soseki Natume’s writing style ranges from exquisitely detailed prose to a more descriptive approach, employing diverse methods depending on the work. At times, it also reveals a remarkable sense of humor. In particular, examining the essays and diaries he left behind reveals his exceptional sense of humor.

Soseki, who had a voracious appetite, meticulously recorded the contents of his meals and his impressions in his diary, and reading these entries is truly fascinating.

What did Soseki, the epicure think of Kyoto cuisine?

In the case of zenzai

Although Soseki Natume suffered from severe gastric ulcers during the latter half of his life, surprisingly, his taste in food leaned toward Western cuisine, and on top of that, he was an absolute sweet tooth.

Soseki himself wrote the following in an essay titled “The Life of a Writer” published in the Asahi Shimbun: “I cannot eat plain food like a drinker of sake. I prefer rich foods. Chinese and Western cuisine are quite good. I have no desire to eat Japanese cuisine.

Admittedly, my palate for Chinese and Western cuisine isn’t so refined that I insist on eating only at certain establishments. My taste is childish; I simply prefer greasy foods. I don’t drink alcohol. I think a single cup of sake is quite good, but after two or three cups I can’t drink anymore. Instead, I eat sweets.”

His favorite foods are “rich, fatty meats,” and he notes that he would rather pick up “simmered ganmodoki” with his chopsticks than plain tofu.

Though he was a lightweight who turned bright red after just one-shot glass, he had a weakness for sweets – cream puffs (he loves them so much he’d hided them from the kids and eat them all himself), ice cream (so rare in the Meiji era that we had a machine at home), sugar-coated bean snacks, monaka, yokan, and white peaches.

Though Soseki Natume’s daily diet was like that, he visited Kyoto four times during his lifetime.

The very first time was the summer of 1892, the second time was the spring of 1907, the third time was the autumn of 1909, and the last time was the spring of 1915.

On his second visit to Kyoto, Soseki wrote an essay titled “The Night I Arrived in Kyoto.” In this essay, Soseki reminisces fondly about his first trip to Kyoto with his close friend Shiki Masaoka, while also writing about his inability to hide his bewilderment at the unfamiliar sights and customs of Kyoto.

“Even as it is, Kyoto is a lonely place. The houses lining the narrow street, cramped on both sides, are all black. Every door is chained shut. Here and there beneath the eaves, large Odawara lanterns hang. In red, they bear the word “zenzai.” Beneath the deserted eaves, I wonder what the red zenzai is waiting for.”

At that time, Kyoto would fall silent at night, with doors shut tight and light extinguished.

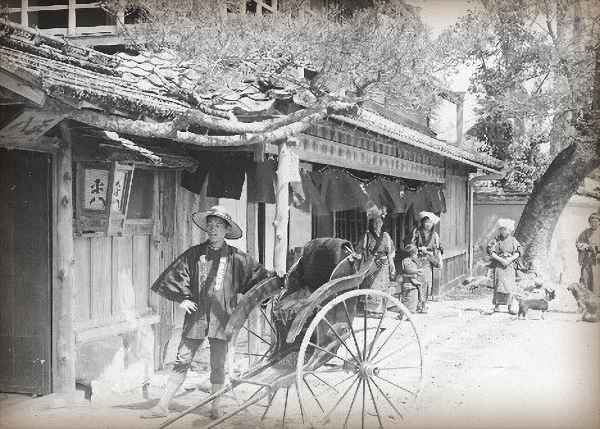

Rocked by the rickshaw, Soseki spotted the lone light of an Odawara lantern.

Soseki notes that the red characters on that Odawara lantern read “zenzai.”

This zenzai also held memories connected to his late dear friend Shiki Masaoka.

Soseki continues.

“The first time I came to Kyoto was about fifteen or sixteen years ago. At that time, I was with Shiki Masaoka. Upon arriving at a house called Hiragiya in Fuyacho and going out with Shiki to see the night sight of Kyoto, the first thing that caught my eye was this large red zenzai lantern.”

“Seeing this great lantern, I somehow felt this was Kyoto, and it has never moved from the day in Meiji 40 now. Zenzai is Kyoto, and Kyoto is zenzai – that was my first impression then, and it remains my last. Shiki is dead. I have still never eaten zenzai.”

Shiki Masaoka

Kyoto’s zenzai seems to be equivalent to Kanto’s shiruko.

Soseki, of course, and Shiki Masaoka also had a weakness for shiruko, and both wrote about it in their diaries and essays. (Soseki: “I ate too much shiruko”; Shiki: “The Shiruko Party,” etc.)

It’s not quite accurate to say zenzai is a Kyoto specialty, but around 1907, there may have been specialty shops selling zenzai in Teramachi and Shin-kyogoku.

In Kansai, zenzai refers to sweet red bean soup with whole beans and a broth-like consistency, while Kansai shiruko refers to sweet red bean soup with smooth paste and a broth-like consistency.

In contrast, in the Kanto region, sweet red bean soup with liquid is called “shiruko”, while sweet red bean paste with grains is called “inaka-shiruko.” In Kanto, “zenzai” seems to refer to sweet red bean paste without liquid served alongside mochi or similar items.

Considering these points, it seems likely that Soseki had no idea what Kansai-style zenzai was like.

Zenzai

In the case of Yamabana Heihachi Tea House

Whenever Soseki Natume visited Kyoto, he invariably made frequent visits to Yamahana Heihachi Tea House, a teahouse along the Saba Highway leading to Wakasa.

Yamahana Heihachi Tea House is a long-established teahouse with over 450 years of history, once serving as a resting place for travelers journeying along the Saba Highway.

They changed their straw sandals here, bathed, and wolfed down barley rice with grated yam before continuing their journey.

Present-day Yamahana Heihachi Tea House

Famous barley rice with grated yam

Heihachi Tea House in Meiji era

The signature dish that has remained unchanged since the founding of Heihachi Tea House is barley rice with grated yam.

Grated Tamba-grown yam mixed with kombu and bonito dashi, then poured over barley rice – this barley rice with grated yam remains an unparalleled specialty dish of northern Kyoto, unchanged through the ages.

Well, Soseki first visited this shop during his initial trip to Kyoto, accompanied by Shiki Masaoka.

It was the summer of 1892.

It is recorded in his dairy that they had eaten river fish cuisine at that time.

The next time he stopped by this teahouse was in February of Meiji 40.

This was when Soseki signed an exclusive contract with the Asahi Shimbun and became a professional writer.

He was 41 years old.

On February 10th, he visited the shop with the haiku poet Kyoshi Takahama and once again had river fish cuisine for lunch.

This trip to Kyoto left a deep impression on Soseki, and based on it, he began serializing his first work as a professional writer, “The Poppy.”

The name of this shop appears in the opening dialogue between the two main characters in “The Poppy.”

“Today I should have spent the whole day at the Hirahachi Tea House at the mountain’s edge.” (From “The Poppy”)

Furthermore, he went on to publish the so-called first trilogy: “Sanshiro,” “Then,” and “The Gate.” The story of the teahouse’s cuisine is also chronicled in “The Gate.”

“Sometimes I’d go all the way to Heihachi Tea House and sleep there all day. The I had my mistress grill some skewered river fish that tasted awful, and drank sake. That mistress wore a hand towel on her head and had on what looked like indigo-dyed trousers. (“The Gate”)

Soseki, who preferred rich flavors, found the mild river fish dishes somewhat unsatisfying.

However, the barley rice with grated yam seemed to suit his taste perfectly, and that was likely why he visited this restaurant so often.

At the present-day Hirahachi Tea House, it seems that instead of river fish, the dish served with barley rice and grated yam has changed to sashimi of guji, a high-grade fish from Wakasa.

Uji’s Buddhist Tea Cuisine and Soseki

In the early spring of 1915, the year before his death, Soseki visited Kyoto to recuperate from nervous breakdown and a stomach ulcer.

The dairy at that time meticulously records the details of meals during his stay in Kyoto.

The day after arriving in Kyoto, he accepted an invitation from Issotei Nishikawa, who had welcomed Soseki, and ate his fill of kaiseki cuisine at “Shosei” in Tomikoji Oike.

The meal consisted of grilled carp, sweet-braised carp, sea bream sashimi, simmered sea bream, shrimp soup, rice, and sake, yet Soseki still noted it was “insufficient.”

Looking at his dairy, Soseki heads straight to the home of Seifu Tuda, a painter who is also a disciple and will be taking care of him during this stay in Kyoto.

Soseki requests his favorite foods at Seifu’s house.

Canned goods, chicken, ham, bread, chocolate, rice topped with yuba, tofu, and mozuku seaweed, etc.

The next day, Soseki visited Uji, guided by Seifu.

At that time, he was eating shojin ryori at the vegetarian restaurant “Hakuan-an” in front of Manpuku-ji Temple.

Fucha cuisine refers to vegetarian dishes originating from China.

This “Hakuan-an” continues to operate to this day.

Fucha cuisine

Soseki recorded his impressions of the Buddhist vegetarian meal in his dairy.

“Lunch at the temple gate’s vegetarian restaurant – dishes without any fishy taste. So many dishes I couldn’t finish them all.”

“Couldn’t finish them all,” he wrote, yet the simple vegetarian cuisine apparently didn’t suit his taste. After returning home, he had his preferred dishes prepared at the inn where he was staying.

Duck breast, sea bream roe, raw cucumber with bonito flakes, shrimp soup, sea bream sashimi, Kawamura sweets.

So far, we’ve taken a brief look, but it seems that the delicately seasoned Kyoto cuisine itself didn’t particularly suit Soseki Natume’s palate.

The regional differences between the Kanto and Kansai regions during the Meiji and Taisho periods were so vast that they are unimaginable today.

For example, in Soseki’s Botchan, there is a scene at the beginning where the maid Kiyo asks the young master, “Is Matuyama beyond Hakone? Or is it this way?”

Furthermore, his dairy recorded that when Ryunosuke Akutagawa first visited Kyoto his foster father, who accompanied him, exclaimed with emotion, “This is the first time in my life I’ve been west of Hakone.”

Under such circumstances, Kyoto cuisine – let alone Kyoto culture itself – would have been quite unfamiliar to Soseki Natume, a native of Edo.

Even so, Soseki’s voracious appetite is truly astonishing.

His stay in Kyoto in 1915 was specifically for recuperating from his chronic nervous breakdown and stomach ulcer. On top of that, Soseki also suffered from severe diabetes.

Despite this, he kept shoveling rich food into his mouth, so it’s hardly surprising that his dying words were, of all things, “Give me something to eat.”

Soseki is often portrayed solely as a sensitive and difficult man, yet he also possessed this distinctly human, humorous side.

References

1: Father: Soseki Natume by Shinroku Natume Bunshun Bunko 1982

2: The Living of a Writer” by Soseki Natume Asahi Shimbun 1912

3: Arriving in Kyoto at Dusk” Complete Works of Soseki Natume Chikuma Bunko 1988

4: “The Poppy” by Soseki Natume Shinchosha Bunko 1980

5: “The Gate” by Soseki Natume Shinchosha Bunko 1978

6: “The dairy” Chikuma Shobo Complete Works of Soseki Natume 1971

Author

つばくろ(Tsubakuro)

I was born and raised in Kyoto and am a native Kyotoite.

When I was young, I longed to visit Tokyo and Osaka, which are more bustling than Kyoto, but as I have gotten older, I have come to appreciate Kyoto a little more.

In this site, I will introduce you to some of the best places to explore Kyoto's food that you might otherwise miss at first glance.